Newton doesn’t deserve the Whole Credit for Light

Chronicles of Pre-Newtonian Light

Every cultural civilisation had, in some form or the other, their very own version of a theory of light.

These were based on the religious and metaphysical ideals prevelant at the time in the concerned geographical region.

For instance, the Egyptians believed that light was the activity of their god Ra seeing. When Ra’s eye (the Sun) was open, it was day. When it was closed, night fell.

The earliest systematic studies of light, however, are attributed to the Greeks.

Greeks & Atomists

In the antiquity, study of light was directed by the study of vision.

In particular, we know of the Atomists who reduced every sensation, including vision, to the impact of atoms from the observed object on the organ of observation.

But even still, there were different schools of thought among atomists.

Democritus (460 BC–370 BC) & Epicurus (341 BC–270 BC)

Democritus was an Ancient Greek pre-Socratic philosopher who first formulated an atomic theory of the universe.

Democritus’ theory of vision was based on perception.

By this he meant that the visual image did not arise directly in the eye, but the air between the object and the eye is contracted and stamped by the object seen and the observing eye. The pressed air contains the details of the object and this information is transferred to the eye.

This combined notion of images streaming from objects and air imprints, he believed, gave us the resources to account for the perception of the relative size and distance of objects, not just their characteristics.

Epicurus was another ancient Greek philosopher, who founded the influentual philosophy of Epicureanism.

He on the other hand, proposed that atoms flow continuously from the body of the object into the eye. However the body does not shrink because other particles replace and fill in the empty space.

This was, however, in direct opposition to Plato’s doctrines.

Plato (428 BC –328 BC)

Plato is arguably the most famous ancient celebrity.

But we aren’t the only ones in awe of his ideas. In Athens, Plato founded the Academy, a philosophical school where he taught the philosophical doctrines that we now know of as Platonism. With this, he attracted a whole lot of students like Aristotle and Euclid, who were influenced by his teachings.

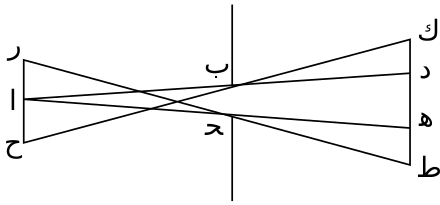

Plato and his followers advocated an alternate theory of vision. One in which light consisted of rays emitted by the eyes.

The striking of the rays on the object allows the viewer to perceive things such as the color, shape, and size of the object. According to Plato, our vision is initiated by our eyes reaching out to “touch” or feel something at a distance.

Illustration depicting emission theory of light

(Source : https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Emission_theory_(vision))

This extramission theory of light was unchallenged for a whole millenium until Alhazen proved it to be wrong.

That too decisively.

Euclid (before 300 BC)

Euclid is called the father of Geometry for a reason.

Yet, the work of the most prolific mathematician of the antiquity spans much more than just ‘Elements’, his treatise on the subject. His ‘Optics’ is the earliest surviving Greek treatise on perspective. It includes an introductory discussion of geometrical optics and basic rules of perspective.

‘Optics’ follows the same methodology as ‘Elements’ and gives a geometrical treatment of the subject.

Euclid, being a fellow of Plato’s, believed inextramission and his theory of vision is founded in the following postulates:

Rectilinear rays proceeding from the eye diverge indefinitely.

The figure contained by the set of visual rays is a cone of which the vertex is at the eye and the base at the surface of the object seen.

Those things are seen upon which visual rays fall and those things are not seenupon which visual rays do not fall.

Things seen under a larger angle appear larger, those under a smaller angleappear smaller, and those under equal angles appear equal.

Things seen by higher visual rays appear higher, and things seen by lower visual rays appear lower.

Similarly, things seen by rays further to the right appear further to the right,and things seen by the rays further to the left appear further to the left.

Things seen under more angles are seen more clearly.

Unlike the scholars who preceded him, Euclid did not define the physical nature of these visual rays. As a mathematician, he simply used the principles of geometry and discussed the effects of perspective and the rounding of things seen at a distance.

Nevertheless, Euclid had restricted his analysis to that of just vision.

Hero of Alexandria (10–70)

Following the most prolific mathematician on antiquity, we have the greatest inventor of antiquity - Hero of Alexandria.

Hero extended Euclid’s principles of geometrical optics to consider the problems of catoptrics. Catoptrics deals with the phenomena of reflected light and image-forming optical systems using mirrors.

Hero was the first to formulate the principle of the shortest path of light.

According to him, light from a point A to another point B within the same medium, follows a path that is shortest. On this basis, he showed that when light reflects from a surface, angle of incidence is equal to the angle of reflection. In other words, Hero derived the law of reflection by his principle of least distance.

Only 1,000 years later would Alhazen expand the principle to both reflection and refraction. And 1500 years had to pass by for Hero’s principle of least distance to be eventually replaced by the principle of least time by Pierre de Fermat in 1662.

In its contemporary form, enunciating that the optical path is stationary.

Ptolemy (90–168)

By this time, another polymath had started taking interest in the intricacies of light.

Ptolemy wrote ‘Optica’ in which he discussed the theory of vision, reflection, refraction, and optical illusions.

The work is divided into three segments :

- Book II - Direct and binocular vision.

- Books III-IV - Reflection in plane, convex, concave, and compound mirrors

- Book V - Refraction

With Ptolemy, for the first time in history, the concept of a field of view emerged. Instead of considering visual rays as discrete lines as postulated by Euclid, he considered them forming a continuous cone.

The last part of his treatise contains the earliest known table of refraction from air to water.

To find this out, Ptolemy had to carry out careful experiments on refraction.

From these he concluded that, for light propagating from one medium to another, the ratio of the angle of incidence to the angle of refraction was constant and depended on the properties of the two media.

He thus derived the small angle approximation of the law of refraction.

Ptolemy also claimed that size and shape were determined by the visual angle subtended at the eye combined with perceived distance and orientation, an idea not considered hitherto.

Ptolemy divided illusions into those caused by optical errors and those caused by errors in perception.

The salient feature of Plotemy’s work on light is the backing up of his theory by experimental results and whenever possible, by the construction of suitable apparatus.

‘Optica’ influenced the even more important work of Alhazen in 11th century.

Islamic Period

Al-Kindi

Father of Arab philosophy, Al-Kindi was also pursued studies in optics and the theory of vision.

Al-Kindi proved Euclid’s axiom of straight rays of light experimentally by considering the shadows projected by different opaque objects. He sided with Ptolemy while considering the geometry of visual cone, believing it to be a cone of continuous beam of radiation similar to that used by latter.

The philosopher’s work on optics significantly influenced the Islamic and Western optics throughout the middle ages.

Ibn-Sahl

Snell’s law was actually discovered 600 years earlier by a Persian mathematician, Ibn-Sahl.

Ibn Sahl used this law to derive lens shapes that focus light with no geometric aberrations, known as anaclastic lenses. He is the first Muslim scholar known to have studied Ptolemy’s Optics. In 984, the mathematician wrote a treatise On Burning Mirrors and Lenses which discussed the parabolic and elliptical burning mirrors. Ibn Sahl also presented an analysis of how hyperbolic glass lenses bend and focus light.

Interestingly, he was also the one who designed convex lenses that focus lights rays that are parallel, which can cause an object to burn at a specific distance.

Alhazen

We finally come to the greatest physicist between Archimedes and Newton.

Ibn al-Haytham, commonly called Alhazen was the first to explain that vision occurs when light reflects from an object and then passes to one’s eyes, and to argue that vision occurs in the brain. He was also the first person to follow the scientific method an entire 5 centuries prior to Renaissance.

Alhazen’s seminal work is Kitab al-Manazir (Book of Optics), a treatise on optics written from 1011 to 1021.

Comprising seven volumes, the book was the first comprehensive treatment of optics and covered subjects such as the nature of light, the physiological treatment of eye, and the bending and focusing properties of lenses and mirrors.

This book was a stepping stone in the transition from the Greek ideas about light and vision to the modern optics.

- Alhazen’s argument

Alhazen did the unimaginable.

He disproved Euclid’s theory.

He carried out a simple experiment in a dark room where light was sent through a hole by two lanterns held at different heights outside the room. Alhazen could then see two spots on the wall corresponding to the light rays that originated from each lantern passing through the hole onto the wall.

Then he covered one lantern, which resulted in the bright spot corresponding to that lantern disappear.

Thus concluding that light, infact, does not emanate from the human eye.

It is only when objects such as lanterns emit light which travels from these sources to our eyes that we can really see them.

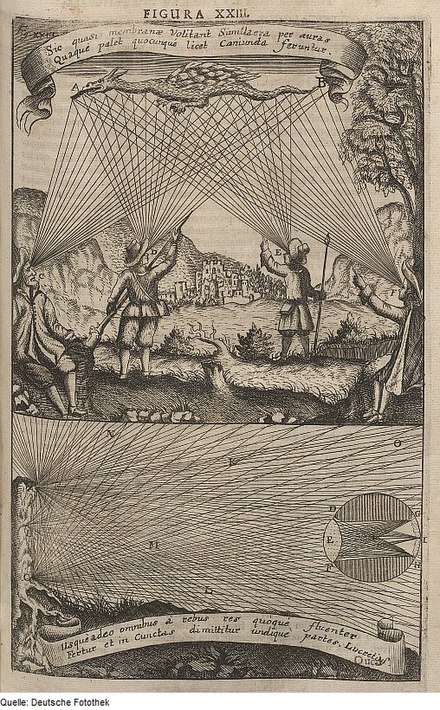

Based on such experiments, he invented the first pinhole camera and explained the upside down image formation in the same.

Alhazen’s pinhole camera

(Source : https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pinhole_camera)

- Mechanism for Magnification

Alhazen may not have invented the telescope, but did explain how a lens worked as a magnifier.

He correctly deduced that the curvature of the lens, produced the magnification and concluded, quite surprisingly, that the magnification takes place at the surface of the lens, and not within it.

Alhazen’s Book of Optics was translated in Latin at the end of twelfth century under the title De Aspectibus. The Latin version of De aspectibus was translated at the end of the 14th century into Italian vernacular, under the title De li aspecti.

This would remain the single most influential work on optics till Newton’s Opticks published in 1704.

Alhzen’s systematic probings into the workings of light has earned him the title of First Scientist from many.

Science comes to Europe

Kepler

Most know Johannes Kepler for his laws of planetary motion.

Though these would prove crucial for Newton’s law of gravitation, it does not undermine the fact that Kepler was a key figure in the theory of light and vision as well.

His interest in the subject appears to have originated in his observation of a solar eclipse on July 10, 1600 by means of camera obscura.

Camera obscura refers to the pinhole camera that Alhazen had worked on as well.

- Kepler’s solution to Brahe’s Problem

Tycho Brahe (1546–1601) had made an interesting observation.

He had observed that the angular diameter of the moon appeared to be larger during a solar eclipse when observed through the pin-hole camera than when observed directly. Kepler felt that this anomaly could not be explained without a full understanding the camera obscura. He thought that the finite diameter of the pinhole should be responsible for this anomaly.

Kepler discovered the solution by an experimental technique.

Wherein he stretched a thread through an aperture from a simulated luminous source to the surface on which the image was formed.

He traced out the image cast by each point on the luminous body. This procedure allowed him to see the geometry of radiation in three-dimensional terms.

In this way, Kepler was able to formulate a satisfactory theory of radiation through apertures based on the rectilinear propagation of light rays.

Kepler did not stop at explaining Tycho Brahe’s problem of seemingly variable lunar diameter.

In 1601, he noted that eye itself possesses an aperture and should be treated in the same way as the aperture in a pinhole camera and subsequently published his theory of vision in 1604 as Astronomiae Pars Optica (The Optical Part of Astronomy).

In it, Kepler described the inverse-square law governing the intensity of light, reflection by flat and curved mirrors.

As mentioned earlier, Kepler also extended his study of optics to the human eye, and is generally considered by neuroscientists to be the first to recognize that images are projected inverted and reversed by the eye’s lens onto the retina.

With the exception of law of refraction, Astronomiae Pars Optica is generally recognized as the foundation of modern optics.

Descartes

Until Kepler, understanding vision guided the study of the nature of light.

René Descartes (1590–1650) was the first person to explore intrinsic nature of light and the laws of optics for themselves. Descartes’ main contribution to optics is his book Dioptrics that was published in 1637. It deals with many topics relating to the same.

For him, it was ‘the stick of light’ that allowed a blind person to discern his environment through ‘touch’.

- Descartes’ law of refraction

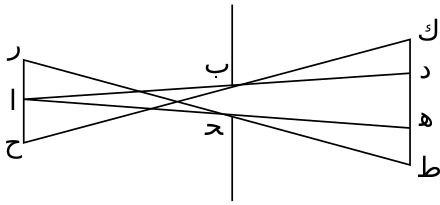

Descartes used a tennis ball analogy to derive the laws of reflection and refraction of light. His essay on optics is the first published mention of this law.

The credit of the discovery of the law of refraction, however is given to Willebrord Snellius (1580–1626) who derived it using trigonometric methods in 1621. But it must be noted that Snell did not publish his work in his lifetime.

Light ray following Snell-Descartes law

(Source : https://personal.math.ubc.ca/~cass/courses/m309-01a/chu/Fundamentals/snell.htm)

Descartes showed by using geometric construction and his law of refraction that the angular radius of a rainbow is 42 degrees (i.e., the angle subtended at the eye by the edge of the rainbow and the ray passing from the sun through the rainbow’s centre is 42°).

Descartes published the law of refraction 16 years after Snell’s death, as Descartes’ law of refraction.

- Cartesian oval and Aplanatic Lens

Cartesian oval is a quartic curve consisting of 2 ovals.

It is the locus of points that have the same linear combination of distances from two fixed points. Descartes discovered if the ratio of distances from these fixed points (called foci) are chosen so as to match the ratio of sines in Snell’s (Descartes’) law, an interesting property emerges. Using the surface of revolution of one of these ovals, it is possible to design a lens with no spherical aberration.

These lenses are called aplanatic lenses.

Wait ! There’s more…

From here the things get spicy.

And by spicy, I mean a crisis. And factions. Factions which argued on the fundamental nature of light.

But it was only through these gruelling battles, that the classical ultimately gave way to the quantum.

References

- Optics in Our Time by Mohammad D. Al-Amri, Mohamed M. El-Gomati, M. Suhail Zubairy

- Light and Blindness in Ancient Egypt by Ana Maria Rosso

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ptolemy

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ibn_Sahl_(mathematician)

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ibn_al-Haytham

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Johannes_Kepler

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ren%C3%A9_Descartes

- Weisstein, Eric W. “Cartesian Ovals.” From MathWorld–A Wolfram Web Resource. https://mathworld.wolfram.com/CartesianOvals.html